By Brian Birmingham

Q: You’ve seen a lot of changes take place in ISKCON (International Society of Krishna Consciousness) over the years, at least in North America. What are some of the biggest changes the institution has made, in your estimation? What things have not changed, or need changing?

A: I joined ISKCON in 1978, just when they instituted the zonal guru system. Under this system, eleven men were named to give initiation within their own zones. This was the biggest change I observed in ISKCON, and probably the biggest change in ISKCON’s short history. I remember being there when Ramesvara announced the plan to a packed Los Angeles temple room. It was unwelcome for most of the disciples of Srila Prabhupada. Some felt Prabhupada should be the only guru even though he was no longer present. They thought any future disciples should be connected to Prabhupada, even if someone else did the initiation ceremony. Others believed all Prabhupada disciples should become gurus and initiate their own disciples. Things split in that direction, because within ten years the GBC had named many more men to become gurus.

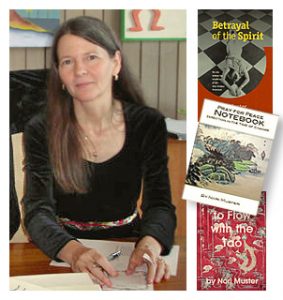

Nori Muster

One thing that has not changed is the place of women. As far as I know, ISKCON still has no women gurus, and they do not allow women to give the morning Bhagavatam classes or lead the morning kirtans. I like to believe they stopped arranged marriages, since I’ve spoken to ISKCON women who told me their assigned husbands beat and raped them. As far as the children, they did change the rules, so children are now allowed to live with their families. That’s one good change.

Q: If there was one thing that you would recommend that that the institution could and should change right away, then what would that one thing be?

A: It’s none of my business since I’ve left the organization. However, when I was a member, we tried to be more open about the truth in the ISKCON World Review. From 1986 to 1988 we published articles, interviews, and editorials on a variety of issues, including the guru reform movement, the gurukula, changes in the BBT, and the murder of Steven Bryant (Sulochan). However, it was the 1980s, and the organization was not ready for that. The GBC kept trying to make us stop writing about ISKCON’s problems. They wanted us to go back to printing only good news, so we resigned. If we had kept going, they probably would have found a way to fire us. However, I still believe sunlight is the best disinfectant, and wish the organization would be more open about airing their internal issues with their members, and the public. We just knew way too much in the PR office we were not allowed to talk about. It seemed awkward and unbalanced. Thanks to covering up the secrets, I left ISKCON with a load of guilt that took years to resolve.

Q: In other words, you’d recommend greatly enhanced levels of transparency and accountability, both within the organization itself as well as in its public-relations dealings? Do I understand you correctly?

A: Yes, I support transparency and accountability. Most of what I know about ISKCON these days is from what people tell me. Lots of people contact me after reading my book or finding my website. Some of the things people say make me think things are still a big mess in ISKCON. Let’s compare that to my undergraduate college. My college has a great reputation and always scores in the top ten public colleges. However, if my college had ongoing scandals and a bad reputation, I would feel embarrassed to tell people that’s where I got my degree. It’s the same for ISKCON. I spent ten and a half years in ISKCON and wish the organization would get it together so I could feel proud of them. I feel they’re still too secretive and defensive about their issues.

Q: What do you think about the ongoing “Hiduization” of ISKCON, and the emphasis placed (in recent years) placed upon outreach and evangelism to the Indian immigrant community? I thought that ISKCON is a non-sectarian spiritual society. Why are they identifying as “Hindus” now?

A: Over the years I watched ISKCON go downhill under white American leaders. About the time I left, 1988, I started to think Hindus could probably do a better job of running it. It is, after all, their religion. They grew up in the religion, while most of us grew up as Christians or Jews. As long as the Hindus are honest and treat everyone fairly, I’m all for it. I would hate to see the whole thing break down.

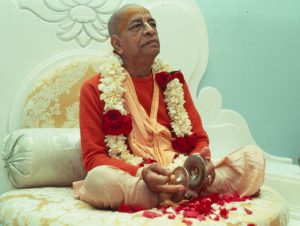

Srila Prabhupada

Q: Thank you for your time and help. I’m going to conclude this interview now.

Note: Nori Muster is the author of “Betrayal of the Spirit: My Life Behind the Headlines of the Hare Krishna Movement” (University of Illinois Press, 1997), “Cult Survivors Handbook: Seven Paths to an Authentic Life” (2010), and “Child of the Cult” (2012). She was an ISKCON member from 1978-1988, then earned her Master of Science degree at Western Oregon University in 1991 doing art therapy with juvenile sex offenders. She is currently a freelance writer and adjunct professor, based in Arizona. Muster also has a website for cultic studies information.

I have occasionally attended Kirtan at the ISKCON temple for the D.C. region. The president of the temple is a woman, though I do not know how that fits in the guru structure. The community is almost entirely Indian American and the temple functions as one of the larger Vaishnava temples in the Washington area.